Men of Eagles is a sprawling compilation of tales that depicts the sorrow and triumph of an incredibly complex time, the Napoleonic Age.

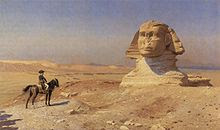

In this preview, I offer the tale of two men whose intertwining lives couple together to irrevocably shape their world amidst the sands of Egypt

In this preview, I offer the tale of two men whose intertwining lives couple together to irrevocably shape their world amidst the sands of Egypt

A Father Loved, A Glory Stolen

"In peace, sons bury their fathers; in war, fathers bury their sons." Herodotus

March the 8th, 1800

Syria

"You see, we do not particularly care for your plight. However, we imagine that there may be a chance for mutual gain in all of this."

The voice crept quietly through a smoke-clouded room. Suleiman al-Halabi listened intently, yet was plagued by despair. The man who had spoken, a representative of the region's Bey, held little compassion in his voice. In fact, al-Halabi did not even know his name. The entire situation was quite singular. The student had traveled miles to petition the government. However, upon arriving at the meeting hall, he had been briskly escorted through the maze-like halls of the building and thrust into a murky room. As soon as the door had been clasped behind him, an official began to speak. In a gesture indicating the height of rudeness, the other man had not offered an introduction. Men had been killed for less, yet the slighted in this case held little power of retribution. In fact, he was here, amid the smoking haze of a hostile government, in order to beg for a life. Further, the rescue of this life called for any humbling he must endure. And so, Suleiman al-Halabi, ashamed for his honor, listened intently to the mysterious official, who continued, oblivious to his listener's shame.

"Yes, your situation is commonplace and of little concern for us. If he had been wiser, your father would not have fallen into his current problems. Under normal circumstances, we have little concern for a man with so little foresight. As it is, however, we have chosen you and perhaps we shall both gain from your father's troubles."

As the official had said, his father's situation was commonplace. Suleiman al-Halabi had been born twenty years previous in Kukan, one of the countless villages in the expansive Ottoman Empire. His family had bid him to leave Syria, however, to pursue an education amid the mosques of Cairo. He had traveled, dutifully and willingly, to Al-Azhar University and delved into Islamic sciences with great zeal. Allah had truly blessed him. His instructors unanimously praised him for his drive and intelligence, and after completing his third year of courses, the delighted student had returned home expecting a joyous welcome.

All expectations had been dashed, however, upon glimpsing his weeping mother. She had knelt amid the dust of a barren home, all furnishings confiscated. Between incoherent sobs, she gushed a story so pitiful that al-Halabi's cheeks still burned with sorrow. Mohammad Amin, his father, had been desperate to allow Suleiman to remain in university. Because of this, he had sent every last coin to his son to pay for the education that would allow his beloved boy to better himself. The following occurrence was one of tragic, yet familiar circumstances. The government had raised taxes in order to pay for its war against the French invaders. Amin had not been prepared for the unseen expense and was soon heavily in debt. He remained so indebted, in fact, that Ottoman soldiers had ousted him from his home and dragged him to prison. Local law prohibited the confiscation of a dwelling, but all the family's furnishings, livestock, possessions, and other items of wealth had been seized and sold to pay for his arrears. Upon hearing of his father's plight, al-Halabi had become wracked with guilt and resolved to right the situation, by whatever means necessary. This resolution had lead him to the dark inner rooms of this distant meeting hall, confused, yet intrigued, at the unnamed man's vague offer.

As the official continued, the weary student's curiosity was piqued; new plans began to form as he exited the hall into the flashy colors of a Syrian market day.

* * * *

Alexandria, Egypt

Hundreds of miles away, another man was beginning to form strategies as well. General Jean Baptiste Kléber, commander of L'Armée d'Orient sat alone in his study with dozens of pressing tasks. Since command had been forced upon him by General Bonaparte's departure six months previous, he had possessed little time for idle thought. With a sigh, Kléber corrected himself.

It was now First Consul Bonaparte. The man had seized glory and the government in one fell swoop. Chuckling, Kléber recalled that the swoop had not been as calm as had been expected. Bonaparte, a man renowned for his rhetoric, had failed to rouse the Senate. In fact, their cries had almost ended the man's glorious coup before it had even started. No matter, however. Bonaparte was simply one of those men whose stars would continue to rise. Destiny was with him, and he was now the leader of la France, such as it was. And, happily, the nation was once again seeing prosperity. The Directory, a council bedecked with greed, corruption, and inefficiency, had done well to lodge the state in heavy debts. Furthermore, they had allowed the infrastructure of France to crumple. The nation's highways had been crippled, while vagrant groups of robbers roamed the byways, preying on any traveler they could overwhelm. Even the cities were descending into chaos. Street urchins, calling themselves Les Jeunesses Doré, roamed Paris seeking merchants to exploit. Gilded or not, these youths had been causing an uproar amid the capital's populace, and the government had been too inept to assist.

With the rise of Bonaparte, the Directory's problems were no more. Once again, merchants freely and safely transported their goods through the French countryside. The National Guard had restored order over Les Jeunesses Doré, and the country, astoundingly, had repaid its debts in full.

France's prosperity, however, was certainly not mirrored amid the sands of Egypt. Bonaparte had left with no warning, and his conquered lands had suffered as a result of their conqueror's swift departure. The effects were seen almost instantly. The man had left as August drew to a close. The entire army had learned of their commander's desertion and morale fell to a new low. If their leader could not endure the harshness of the land, they surely would not, the men reasoned. Additionally, the logistics of such an abrupt change in command were a nightmare.

For days, the entire French command had scurried around, chaos embodied. They had awaited tranquility, and Kléber, in part, had provided it. Previously, among the plains of Italy and forests of Germany, Kléber had shied away from complete command. To be perfectly candid with himself, he simply did not want the responsibility. However, the General was anything but lazy. It simply seemed a common occurrence that the national razor claimed the lives of commanders who had not lived up to expectations. And thus, Kléber wanted none of this.

Now, however, the situation was altered twofold. Under the Directory, the fear inspired by Robespierre 's Terror had abated. Citizens of the Republic were seldom paraded through the streets to meet death on the scaffold. Thus, this concern had been removed. Additionally, General Bonaparte had left direct orders for Kléber to assume command. There was no avoiding it. And, fortuitously, Kléber had come to enjoy the benefits of control.

Admittedly, the work was strenuous. Chuckling to himself, the man remembered an occasion the previous week. He had been pacing his chamber and happened to glance into a forgotten corner and jumped instinctually. A man had been starring back at him. Troubled, the General realized it had been a mirror. With shock, Kléber had examined his complexion. His wavy blond hair had been nearly been bleached white by the sun; his skin, once drawn and pale, appeared leathery and rigid. Similarly, his frame had narrowed to almost a sickly slenderness. With pride though, Kléber saw that his height had not been diminished by the sun of the pharaohs. The instance was telling though. The man had worked in deplorably arduous conditions for more than two years.

Yet, was their toil not providing some fruit? Egypt, although exotic, was quite oblivious to the modernity of continental Europe. France was responsible for providing advances in technology and economics to this land. However, the ravages of war hurt Egypt as well. As a result, the feelings of the population were entirely mixed, as the report on Kléber's desk seemed to underscore.

Once again, the populace had risen against their occupiers. This time, the rebellion swelled through Cairo. "A rather troubling development, really," Kléber mused. The General truly wished that he could force the inhabitants of these lands to see reason. France was at war with Great Britain; he was not here to terrorize the Egyptians. Yet, as of late, he had not been able to assure the Egyptian populace of his desire for friendship. But, the General had resolved to continue in this task.

However, the recent rebellion certainly coincided with other international developments, although the general doubted the two events coincided. Several months ago, realizing the futility of remaining in Egypt without supplies from Europe, Kléber had approached the British to discuss an armistice. Commodore Sydney Smith of His Majesty's Royal Navy had certainly proved to be accommodating. With the defeat of the French armada at the Nile, L'Armée d'Orient was essentially cut off from all resupply. As such, Kléber had feared Smith would be harsh in his terms. However, the man was willing to allow the French to withdraw honorably without harassment. It was quite fortuitous that an enemy would see reason in ending this conflict so far from the combatants' homelands. Sadly, Smith's superiors did not view the situation quite so clearly. A second document lay on Kléber's desk that attested to this fact.

Admiral Lord Kieth had sent his respects, along with a seemingly sardonic toast to the General's health. After these pleasantries, however, the document's true value was revealed. The Admiral was refusing to ratify Smith's treaty, and the conflict would continue. Upon hearing the news, Kléber had slammed his thick hand onto the unforgiving wood of his desk. The moment was rage was unpreventable; Kléber had needed an evacuation. His supplies would eventually run out; additionally, the men's morale would give way as well. The Admiral's refusal was justifiable strategically. However, Kléber's forces were still formidable, and the British would certainly lose good men in the continuing struggle.

"Lucky for them the Turks will bleed first," Kléber whispered to himself. The man stood and sauntered over to his map table. The expanses of Egypt and the Holy Land were arrayed before him. Since the British desired a continuation of the conflict, and the Egyptian populace of Cairo was feeling martial as well, he had resolved to accede to their wishes; war would be had by all. The location remained the only questionable factor. Earlier in the day, Kléber had received a report that a Turkish force, supported by the rebels in Cairo was approaching the village of Heliopolis. While a looming battle was to be anticipated, Kléber questioned whether he should engage this force. While the General possessed ten thousand men for a field army, the enemy marched with over five times that number. On numbers alone, the battle would be a disaster.

Numbers, though, had not decided the previous engagements of the campaign. The French line had continually held against overwhelming odds in all earlier battles. The Battle of the Pyramids had been a spectacle of bravery and tragic slaughter. Murad Bey had led his glorious cavalry again and again across the sands. Each charge had been weathered by General Bonaparte's stalwart soldiers. This had only been possible through the use of the infantry square, which presented an uninterrupted line of bayonets towards the enemy. The undaunted courage of the Mamelukes had been swept away by the discipline and tactics of a new order. Again, the Battles of Abukir and Mount Tabor had seen numerically superior foes humbled by French soldiering.

Now, however, Kléber questioned whether he could continue that success. The men were unanimously weary of the campaign and longed to return home. Yet, it was time to show France's enemies that beleaguered soldiers would continue to achieve glory. Looming over the maps, Kléber realized that the decision had been made; he would march.

Thus decided, action must follow, and the General immediately called for his staff. While he had remained alone amid the maps and reports of his office, he had taken the initiative to order his staff to assemble that morning. Regardless of his decision, his officers had to be informed as to their leader's commands. As such, it was only a matter of minutes for the men to bustle into Kléber's spacious command-room.

Once the last of the men had gathered around the map table, leaving a small amount of space in which Kléber paced, the General glanced at the assembled officers.

"Gentlemen," he began. "As you've likely heard, the Turks have decided La France needs just a bit more practice at soldiering." Quiet laughs pattered around the circle, but mirth was absent from both the joke and its response. Every officer present was aware of the difficulties of their present situation. Without the ability to resupply, French forces in Egypt were slowly deteriorating, and eventually, the situation would reach a breaking point. Kléber and his men were truly in tune to the fact that such a moment may well occur during the coming campaign.

"And so," he continued, "we will meet them. Our scouts indicate that a force of nearly thirty thousand men awaits us at Heliopolis. They are supported by twenty thousand irregular troops." A hidden shudder passed through the hearts of all present. These irregulars were responsible for many of the atrocities wreaked upon Kléber's men over the previous months. Examples abounded of captured French soldiers being tortured to death amid the unforgiving African sands. The general gave no visible sign that he even noticed his men's concern. "French discipline and tactics have continually proved superior to the likes of these tribal warriors, however courageous they remain. We will not wait for the Turks to attack us. Instead, we will march to Heliopolis and once again drive them from this land. Following our victory there, the army will then advance upon Cairo, rid the city and its surrounding villages of the dissidents, and restore peace again to the region. The strategy is simple; the implementation may be a trifle difficult. I cannot spare the garrison forces of Alexandria to march with us. The field army will consist only of the reserves, the ten thousand. Perhaps fate will smile more upon us than Cyrus the Younger." The reference drew smiles from the knowledgeable in the group, while others clearly had not read of the forsaken Greek mercenaries.

Ignoring the bemused expressions of the ignorant among his men, he stopped his pacing. Placing his hands on his hips, he smiled warmly at his men, his comrades in arms. "Anyone opposed to tramping around the desert again?"

Raucous cries of "Vive La France!" resounded through the room. The men had his respect, and he possessed their unwavering loyalty. And so, the General got on with planning his next action.

* * * *

Suleiman al-Halabi grappled with a raging conscious. It was one thing to study ethical conflict. His education had included numerous lectures on Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, as well as plentiful Islamic treatises on the value of ethics. Yet, in the entirety of his life, al-Halabi had truly never come across a situation where his proposed means so strongly conflicted with the purpose of his desired ends. It was imperative to rescue his father; that much was undoubtedly clear. However, was his current course of action the best way to accomplish this? It was certainly the simplest, Suleiman reflected. The Bey's representative had spoken succinctly. His father would be freed upon the completion of the task. Now, al-Halabi was shocked upon recalling that it was only two weeks later, he was on the road, actively following that mission.

The risk involved, however, was astronomically high. Indeed, the punishment for failure would be lethal. Perhaps, al-Halabi could somehow acquire the funds to pay for his father's debts. Logically, this seemed unrealistic. The amount owed was indeed large. His father would languish in prison until such time as the debts were repatriated. Thus, the ethical quandary lay before him.

al-Halabi's camel took no notice of its rider's intense mental battle. Instead, it simply plodded along the sandy byway that traversed the Syrian landscape. Insects scurried among the grains of sand, and carrion birds could even be witnessed searching the land for a meal. al-Halabi's fellow travels continued unaware as well. The merchants in the caravan laughed heartedly at their own foolish jokes, while the cries of an infant emitted from a simple wagon, its parents trying to coo it into peaceful sleep. Indeed, all of nature was oblivious to the student's toils.

Yet, for all his ponderings, al-Halabi could not be oblivious to the world in return. A commotion near the front of the traveler's caught his attention. Straining forward for a glimpse, the student noticed a patrol of Turkish soldiers. Apparently, these men had come upon the traveler's from the opposite direction and were now performing an inspection of their goods. Several had drawn kilijs and violently rustled through the merchants' sacks.

One man, an officer by his gaudy clothing and decorative weapon noticed the inquisitive student. He wheeled his mount, a small horse, towards al-Halabi and quickly closed the distance between them. "A bit too interested, aren't we?" the officer clipped out, rather nastily.

"No sir," replied the student. "I simply have urgent business to take care of and any delay would be most unfortunate."

Wielding his kilij rather close to al-Halabi, the officer offered only a leering glare in return. Then, he motioned to two other dismounted soldiers. Without needing a spoken order, they grabbed al-Halabi and dragged him down from his camel. A shout of protest arose from his throat, but it was quickly silenced as the blade of the officer's kilij found a place against his throat.

"Unforeseen delays can indeed be trifling," spoke the officer quietly. "What is so pressing that you risk the wrath of the government's appointed warriors?"

Although he attempted to remain calm, Suleiman's rushing heart and quivering knees belied his aims. He attempted to speak, but the terror in his heart had clenched his throat as well. Coughing, he tried again. "Sir, examine my missive. I am at the disposal of my Bey. I travel under his authority, with his urgency for speed, and I meant no disrespect." He nodded towards the saddle-pack upon his camel. In response, the officer snatched open the pack's flap and began rifling through its contents. Garments, cooking utensils, and other items fell to the earth amid the officer's search.

Eventually, he found an official looking document, folded and clasped with a wax impression of the Bey's ring. Breaking the seal, the Turkish officer quickly scanned the document. Suleiman was initially surprised that the man could read. Illiteracy was rampant among the army. Apparently though, this man could discern the Bey's missive. Wheeling back to face Suleiman, he adopted a contemplative countenance as he examined the student with new intent. "You certainly don't seem of the assassin's disposition."

"This is my first, and hopefully final, task in that capacity," chuckled al-Halabi nervously. Releasing him, the other soldiers wandered off to harass other members of the caravan, while the officer nodded in thought towards the cowardly student.

"I see. Well, may Allah smile upon your task then, friend." Without waiting for a reply, he too turned to regard al-Halabi's fellow travelers. For his part, the student stooped down and collected his scattered belongings from the sand. Stuffing them back into his pack, he glanced up to the now setting sun. Another hour of travel remained for that day, and hopefully, he would reach Egypt by the onset of June. The student retreated back into his tortured mind.

* * * *

As promised, Kléber and his faithful soldiers had traipsed around the blistering desert in search of a foe. The joviality that had accompanied the initial march had long been dampened in the weeks since. The deplorable conditions of desert campaign had left even the most enthusiastic speechless or hostile. Overcoming the sun provided the greatest challenge. During the day, men would simply drop from the marching lines; sunstroke and dehydration took their toll. This, of course, had caused morale to plummet. It was a terrifying and sickening event to be marching in step with a man and in the next minute, witnessing his lifeless or senseless body drop to the unforgiving sand.

And it was that merciless sand that offered another obstacle in this maddening land. Those tiny grains of grit, miraculously, possessed the inexplicable ability to place themselves anywhere. Sand would enter the men's mouths. It would coat the insides of their boots. Men would empty their hats of the inanimate pestilence. Food, already lessened in quality on campaign, had an inescapable gritty texture. It was truly maddening.

Yet the beleaguered L'Armée d'Orient had endured. Their strength of will had carried them thus far, and their General desperately hoped it would hold in the coming battle. For today, numbers would not be in their favor.

Kléber even chuckled to himself at the absurdity of their numerical inferiority. He sat, astride his mount, overlooking the field of contention. His men were arrayed behind him, and his faithful staff stood, ever watchful and attendant. In opposition, waited the hordes of the enemy. His scouts' reports had proven all too painfully accurate. The Ottoman army numbered over fifty thousand men. To face them, he had only been able to muster ten thousand. Also, as predicted, the forces had converged on Heliopolis. Fittingly, this City of the Sun was bathed in the glorious pre-dawn glow that just caresses the land. Even so, the General knew full well that the gentle heat before dawn would soon be replaced by a scorching blaze. It was imperative for the battle to take place before the heat of the day was unbearable. In this respect, his opponents held the advantage. For centuries, their ancestors had lived among these treacherous sands. They possessed the knowledge needed to survive in the arid heat. Kléber's soldiers, by contrast, had only dwelled in the land of Pharaohs for a few scant years. They were certainly ill-equipped to handle these conditions.

It did not matter, however. In those few years, Bonaparte, and now Kléber, had shown that French martial skill far surpassed its enemies'. Today would be no different. With that expectant, yet weary, thought, the General signaled the advance, and his men stepped forward in glorious cohesion.

A small valley separated the two forces, and the quiet town remained to the east. Kléber hoped it would not come into the conflict. Although a toughened soldier, he truly detested the excesses of a sacked city. War, he viewed, should only be conducted between two professional armies; it was simply a shame to ravish a country's people in the pursuit of war. Discipline would keep his men in line, and the enemy's flight would hopefully prevent any immoderations on their part.

And the enemy now responded to his advance. Across the valley, the Turkish commander signaled his own troops, and the opposing army exploded in movement. For a second, Kléber was distracted by the hurried change. Yet, the General's focus was regained as he witnessed his adversary's predictable strategy. Having emerged from behind the ranks of infantry, a massive charge of cavalry bounded across the sand. He almost cursed the enemy for his constant bravery and steadfast foolishness.

"The line will form squares!" he bellowed towards his men. In response, each unit's individual commanders implemented the order. All down the line, each unit collapsed in on itself. Sergeants rushed through the ranks, vehemently cursing those who lagged behind, their bushy mustaches quivering in their excitement. As each square formed, a highly drilled technique was put into place.

The square consisted of three ranks of men. The first crouched in the sand, their muskets firmly planted in the ground. Next, the second row stooped, a rather uncomfortable position, but necessary all the same. Finally, a third row waited at a third height, their muskets held parallel to the ground. In all, the square was based upon animal psychology. Each row presented a vicious rank of bayonets towards the oncoming foe, the sun gleaming off the freshly sharpened blades. In essence, the square became a hedgerow of deadly steel. No matter the suicidal courage of their riders, the swift Arab ponies would not, in general, throw themselves upon the certain death of the square. The tactic had first been proven in Italy and since been mastered against the Mamelukes. The Turkish cavalry now exploding across the field rode to their doom; it was inevitable.

Although fated for disaster, the Turkish cavalry provided a glorious spectacle. Kléber pitied them, but he could not find fault in their bravery. Each enemy rode, bedecked as a noble. Jewelry adorned everything. The sun glanced off diamonds, rubies, emeralds, amethysts, and other precious stones. Additionally, their swords were without compare. Each kilij had been crafted by a master, and each wielder knew the deadly power of his tool. The blades danced around as their holders waved and thrust them through the air in their ecstasy. Headdresses shown with vibrant hues, and saddles groaned as the supple leather bent to its task. Kléber was truly saddened to await these kings' destruction.

Finally, the General's infantry finished their maneuvers and stood to await the coming storm. In addition to their movements, Kléber had signaled his cavalry. They currently protected the wings but would be no match for the Turkish charge. Individually, no horseman in the world could match the training and grace of a French equestrian, but this fight would not be won on numbers. So, in order to spare their numbers, Kléber ordered them to fall back behind his lines. The enemy's charge would break itself on the immovable wall of his line, and then the cavalry would, in turn, pursue the fleeing enemy to their doom.

While the line infantry and cavalry prepared, the artillery's battle had already commenced. Rolling barrages echoed from the French guns. During the march, it had been found that the heaviest guns simply would not move; their weight propelled each caisson's wheels into the sand. Thus, Kléber had not been able to bring his heaviest canon to bear. It was no matter, however. With each thundering volley, the deadly spheres arched through the sky to land amid the charging foe. The grim display saw men wrenched from their saddles and hurtled to the sand. Other Turks found their animals stricken with terror. Still others emerged, physically unscathed from the onslaught. These valiant men continued onward, their task as yet undone.

And finally, the gap closed, and the true battle was joined. The Arab ponies dashed through the staggered rows of squares, each horseman rendered ineffective by French discipline. Several Turks understood their plight and instantly turned to flee; they received the jeers from their fellows. Kléber even witnessed one massive Turk draw a pistol and shoot down a fleeing comrade. The sight was telling; France truly was fighting a society whose honor remained paramount above all else. Other Turks utilized their weapons against their French adversaries. Realizing that melee was nearly impossible, several cavalrymen produced bejeweled muskets and pistols. Sadly, as the square demanding close cohesion, the enemy never missed, and each puff of smoke was accompanied by a French cry of anguish. These cries mixed with the yells of exultation, the insults of enmity, and the clattering hooves of the Turks. Together, this maelstrom of dissonant sound was maddening in its volume and terrifying in its implications.

From his vantage point atop a small mound, Kléber and his staff witnessed the grisly spectacle. It was fortuitous that he had emphasized the square drill in previous months. Although his men had had ample opportunity to use it in battle, he knew that the formation was critical to success against the Ottomans, and so, he had drilled constantly. That time spent was providing dividends here. The Turks could simply not break his squares. Scores of their horses had been slain, and the galloping enemy horde was slowly being brought low. For his part, the French General wished that these fanatics could be made to see sense. They had no hope of overthrowing French dominance in this way. While his forces had been cut off from Europe, they remained as effective a fighting force as ever. The antiquated style and training of the Turks could not overcome his men. Perhaps this battle would finally instill the enemy with the sense to cease resistance. The General turned to an aide.

"Once their cavalry has retreated, we will advance in square towards the enemy. I want the cavalry back on the wings. They will shield us from the Turk's flanking and are to be ready to charge home if the moment presents itself."

The aide, a mousy man bedecked with a crimson pate and thick moustache, nodded. "Yes, my General," he responded briefly. Then, he quickly wheeled his mount and rode towards Kléber's assembled messengers. He relayed the General's orders, and the messengers, in turn, rode out to deliver the instructions to the divisions' commanders.

Meanwhile, the Turkish cavalry had all but expended itself upon the unyielding squares. Those mounts not wounded were flagging; their charge and subsequent sally into the French formation had left many ponies panting and foaming at the mouth in exhaustion. Their riders either extolled or threatened them into movement, and at length, the depleted and bloodied cavalry began their retreat.

It was at that pivotal moment that Kléber's soldiering instinct took hold. Raising his telescope towards his eye, he scanned the retreated mass of horses. Then, turning his gaze, he took in the waiting enemy lines. While their cavalry were, if foolish, glorious, the enemy's infantry simply looked substandard. Their uniforms were completely mismatched. Many possessed aged muskets, that Kléber doubted would even fire. However, it was not their physical appearances that attracted his attention. Rather, it was their mannerisms. In contrast to the steely, immobile men of the French line, the Turkish infantry was visibly skittish. Men nervously talked to each other, openly pointing toward the retreating cavalry. Others collapsed upon the sand in terror. Their sergeants and officers attempted to maintain order, but it was clear to Kléber that, with only a little pressure, this foe would collapse.

That pressure would be applied twofold. As Kléber viewed the enemy, the first application of terror was beginning. The cavalry had returned to its side of the field; yet, it had not arrived in formation. Instead, the retreating Turks flew pell-mell through the waiting infantry. This chaotic return did not bolster the waiting army; conversely, terror was sown among the ranks of the enemy.

Kléber, from his position, had foreseen this, and was already acting. He sent out another order. This one commanded the men to push forward at the run. While it was difficult to maintain exact formational order, it allowed his army to cover ground quickly, and, in this instance, speed was essential. Thus, it came to pass that the entire French army undertook a controlled charge towards their foes. Advancing with his men, the General turned to regard his staff. Expectant grins donned the faces of each man, and some looked as if they could barely contain their excitement.

He spoke to them. "A little push more, and our enemy will be little more than a rabble."

The redheaded aide spoke up. "That's assuming, sir, that they were organized before." The quip gained polite laughs, and Kléber smiled in return. While war remained an abhorrent necessity, it was pleasant to belong to such a close-knit brotherhood. Returning his attention to the conflict, Kléber again raised his glass. On this occasion, the view was both pleasing and horrific. The sight pleased Kléber because the entire enemy force was disintegrating before his eyes. Discipline had completely abandoned the Turks, and men were fleeing in droves. Concurrently, the sight was sickening. Men were being trampled under the feet of their retreating comrades. Others fought each other for space, and in general, all human ethics had been discarded with the loss of discipline.

"' Vae victis,'" Kléber quoted sullenly. Yet for his melancholy, the General cared more for his own men, a soldier's true responsibility in war. Therefore, he would ensure that these foes would never kill Frenchmen again. As such, he dispatched another messenger, and the French cavalry responded to his call.

While the Turkish equestrians had been glorious, their glory was matched through the disciplined, precise charge of their French counterparts. These men were not warriors; instead, they remained parts of a cohesive whole. They acted in concert, and their action was deadly. Kléber had ordered each flank of cavalry to charge home in union. The ground thundered once more as each side of the French army exploded towards its foe. And victory was attained.

All resistance utterly collapsed with the charge of the French horses. These men, riding mounts without equal, quickly entered the fleeing mass and set to their work. The enemy was cut down like wheat before them, and those who were missed by the blade, met their end under the hooves of the French chargers. In the end, every Turk fled for his life.

Kléber and his staff assembled at his previous post, the mound overlooking the field. Attempting to ignore the grisly sight before him, the General received the reports of his commanders. His men had fought valiantly; but in truth, the victory was the result of a conflict of styles, rather than of individual soldiers. The French had again proven that disciplined order would always supersede courage. All told, the battle's result was staggering. Estimations on Turkish casualties were as high as twenty thousand. Additionally, over five thousand men had been taken captive. In contrast, French losses were less than two hundred. As the numbers were reported, Kléber simply gasped. His victory was total, and further successes waited.

With the disbandment of the Turkish army, the current rebellion to French rule would collapse. Without an organized force to support them, the rebels would be forced to come to terms. The road to retaking Cairo lay open.

And indeed it was. Before another two weeks had passed, Kléber and the French were once again in possession of the great city of Cairo. The "siege" had been as trifle a matter as the Battle of Heliopolis. Although several radicals had attempted to bar the gates, the city's elders had seen sense. They realized that a martial force, who could so easily disband an enemy army five times its number, would have little difficulty in capturing their city. Thankfully, Kléber had not had to resort to taking the city by force. His men had been absent from pleasures and drink for too long; he had feared for the people of Cairo. However, a sack had not occurred.

Yet, not all were placated. Even though the city's elders had been most compliant and heavy penalties were in place for flaunting the French occupiers, many in the city were still enraged. This anger spilled over the morning after the city changed hands.

At the time, Kléber was taking a quiet supper in his new quarters. He had selected a small, airy home. Shutters adorned the windows, but each was opened in order to catch the slight breeze wafting through the city's streets. The General was nursing a small cup of pungent tea and very content with life, when a messenger burst through the door. One of the posted sentries followed him in, maintaining a watchful guard on his commander.

As for the messenger, he was doubled over, gasping for breath, obviously spent from his rapid journey. Upon seeing Kléber's glance, he rose to full height to offer his report. "Sir," he began. "Captain Debuse offers his respects, and begs to report that a riot is in progress at the city's market." The General quickly remembered that Debuse commanded a garrison force several miles away in the commercial district. The city's main market and bazaar were indeed within that space, and provided amble room for a riot to form. The messenger had paused for a much-needed breath.

"Captain Debuse has ordered members of his garrison to assemble. Additionally, he sent for several artillery pieces to be prepared. They are to assemble along the outskirts of the market. He is at your disposal and eagerly awaits your orders, sir," the man concluded. The General mulled over the situation briefly, then stood, donned his hat, and picked up his sabre.

"It seems," he replied, "that Cairo is far from peaceful. I suppose we'll simply have to provide a bit of soothing touch." The remark was spoken with some trepidation. Kléber had once commanded men in repressing the Vendean revolts. The Vendée was a volatile region of France who had defied the Revolution. Its population was composed of incredibly conservative Royalists who had viciously fought against the reforms of the National Assembly. Brutal civil war had raged in the region, and Kléber had led the armies who quelled the region's resistance. Thus, he knew the terrible consequences of civilian resistance against martial force. As civilians possessed little fighting prowess, atrocities were often unavoidable. Yet, order and the rule of law must be maintained. So, the General finished collecting his kit and looked to the messenger.

"Tell your Captain that I am on my way. I will personally quell this riot. Then we can get on with our lives." The messenger nodded and dashed from the room, eager to report the General's words to his commander.

Kléber followed, collecting his staff as he went. Together, they mounted their horses and entered the winding streets of Cairo. As with many antique cities, the streets of Cairo were an abhorrent collection of disease and filth. Graffiti, both ancient and modern, adorned the walls. Beggars and drunkards lay in the dust, and naked children played and hopped through the crowded byways.

For his part, Kléber took little notice. His mind was on the coming struggle. It was one thing to disband an enemy army; each had, seemingly, an equal chance of victory. It was another matter entirely to fight civilians. "Why could these men not remain peaceful," he thought bitterly. The French were not there to harm Egyptians. Rather, the expedition had been conducted to weaken the British holdings in this region of the world. He, and by extension, the men he commanded, wanted no part in harassing the common people. If they would simply grasp this concept, life would be better for all.

The General's musings had left him unawares as he simply rode through the streets. Eventually, he returned to the present and realized that his entourage had arrived at their destination. In front of him was a small plaza. Gathered in that space were rows of waiting infantrymen. They were complimented by three small artillery pieces, referred to as "galloper guns" by their operators. Additionally, a small contingent of hussars stood amidst the waiting force. While not overly numerous, this force would be more than sufficient to end any rabble's resistance. Across the courtyard, a similar collection of staff officers were leaving a white-washed building, Captain Debuse's headquarters.

Leaving his assembled staff to organize the force into marching order, General Kléber trotted across the square. Upon meeting Debuse, they exchanged salutes, and the Captain offered a brief report, which simply reiterated the messenger's tale. In turn, Kléber offered his gratitude for Debuse's swift response, and turned to regard his men.

"Soldiers of France!" he called to them. "You have one duty today. You have license to do nothing else. That duty is to restore order, and I will punish any man who exceeds this duty. We are not animals; you will consider every drop of spilled Egyptian blood to be worth far more than your own. We need show these men that we fight England, not them, in our occupancy of their land. Is this clear?" he bellowed. Cries of compliance echoed from the waiting soldiers. Each held a vast amount of respect for their leader; he had continually led them to glorious victory. His disappointment was akin to highest shame for them. Thus harangued, the men quickly fell into step as their General led them from the square.

The riotous mob was not difficult to find. Kléber's men had only traveled several blocks before the sounds of the rabble reached them. This noise was accompanied by fleeing men and women, eager to escape the coming onslaught. Kléber let them pass; he was not concerned with those who respected the law. Finally, as his men drew upon a large square, bedecked with market stalls, the General viewed the mob.

It truly was a sight to behold. Composed of both men and women, all furious, the mob raged through the market square. Despite the early hour, several held torches, but fire had not spread from them as yet. Additionally, nearly every member was armed with something. Some held muskets, while others waved kilijs above their heads. Still others had broken the flagstones of the street and now walked about, gripping these jagged rocks.

Upon witnessing the arrival of the French, the mob's attention instantly grew focused on the foe. As they advanced towards the entering soldiers, Kléber quickly had his men form line. Additionally, the galloper guns were set up and loaded with grapeshot. Seeing this process, the General inwardly winced at the coming slaughter. Yet, the mob remained steadfast and advanced en masse towards Kléber's command.

"Cease!" he called. "We are not here to oppress you! France and your nation should be comrades, not warring against one another!" The mob took no notice. Some even hurled insults and stones towards him. And then, it was begun. A rolling, combined volley from the artillery pieces and infantrymen rang out.

The result, as predicted, was devastating. Scores of Cairo's populace dropped, caught in the lethal fire. Their comrades seemed to take little notice however, and more rioters charged the waiting line. "Damn you all!" Kléber cried, his voice breaking with emotion. Could they not see their brethren dying? Why must he kill more of this proud nation?

Again, his plea was not heeded, and the unyielding mob was dispatched.

Kléber nearly wept at the waste, but dignity held his composure. Afterwards, the bodies of the rebels were lined up, side by side, for families to claim. The Frenchmen kept their word and treated each fallen Egyptian as precious; no dishonor was done in all the exchange.

Yet, as Kléber resumed his endless tasks the next morning, he remained sick at heart. "There must be a solution to this needless slaughter," he argued futilely. The task troubled him so that he had written two bulletins the previous evening. One called upon the Egyptian populace to see reason. He rationally explained the French purpose for invasion, and begged Cairo's citizenry for friendship. In the second, he asked for advice. He demanded that those with grievances present their cases to him. Perhaps the dispute could be remedied. These papers had been printed and published throughout the city.

The General continued to search his thoughts for an solution. His supper provided none. Similarly, his many meetings that evening gave no clue as to a answer. Finally, as he discussed the merits of a certain proposed bridge with his Chief Engineer, a sentry quietly entered the room.

"General?" the man respectfully interrupted.

Kléber looked up. "What is it?"

The sentry continued. "There is a man here that seeks an audience. He claims to know a way for peace in this land. He is a student in Alexandria."

The news filled the General with expectant joy, and apologizing to the Chief Engineer for the interruption, ordered the man to be shown in.

Thus beckoned, Suleiman al-Halabi, a devoted and loving son, entered the room. It was a very fortuitous that he had read the General's bulletins. It provided access to the man, which otherwise, might have been incredibly difficult to secure. Unaware of his imminent doom General Kléber rose and strode quickly over to him. Stretching out his hand, he took al-Halabi's in his own.

And for a brief, crystal moment, the two patriots locked eyes. One possessed an undying love for his fatherland, the other, a deep, unyielding adoration for a father. In that instant, a connection linked the killer to his victim, and a feeling passed between them. It is not right to call it empathy; the term "understanding" comes nearest. Each man saw the other's passion.

But then the moment was shattered, and al-Halabi ran, a crimsoned stiletto clutched in his fist.

If he was honest with himself, he had no true plan of action. Even striding into the French general's room, Suleiman had not truly known if he would carry out his missive. Yet, the image of his doomed father had guided his hand. And now, the deed finished, he dashed into the dusk, terrified for the future.

Sweat graced his brow as he ran, pell-mell, through the streets. Behind him, he heard vicious shouts and startled cries. Shoving his way through the crowd, he dashed into a small public park. The area, reserved for quiet, contemplative thought was empty at this hour, the philosophers having abandoned the space for the evening. Still frantic, Suleiman threw himself under a shrub and began to pray to Allah as never before. Yet, he could not control his breathing, and as he panted, hot tears of fear coursed down his face.

And then burly hands closed upon his throat.

Once more, the student was on his feet. Now however, he stared into the mustached, frightful face of a French officer. No words were spoken. Suleiman realized with shame that he hadn't even discarded his knife. There was little hiding his guilt as they wrenched the bloodied weapon from his grasp. In fact, al-Halabi found his legs giving way as what little composure he held melted from his soul.

Yet, as the soldiers roughly carried him through the streets, al-Halabi finally found a sense of peace. Regardless of his fate, his beloved father would once again walk amid his people; a condemned student had traded his own freedom for his father's- a fallible life for unfailing love. Smiling, Suleiman al-Halabi found that such an exchange possessed no equal.

Historical Note by the Author:

First, I have used Western spellings and American measurements to avoid confusion.

Additionally, it is simple to cast ignominy upon al-Halabi. Yet I ask that the reader consider his position. Who among us, when facing this student's piteous position, would not at least consider performing the task which this man did? For his deed, al-Halabi, a devoted and loving son, was tortured and publicly executed by impalement. General Kléber became a worthy martyr for the people of France, and his heart lies amidst the heroes of his nation at Les Invalides.

On an intriguing final note, the General died on June the 14th, 1800. His close friend, General Louis Desaix, was also slain at the famed Battle of Marengo on this same date.